News

By Alan Smith, Meteorologist Updated 18 days ago July 10, 2025

North American Monsoon, Explained

The North American Monsoon is a seasonal circulation of subtropical moisture that develops over Northern Mexico and extends into the Southwest U.S. during the summer months. This pattern results in frequent thunderstorms and abundant rainfall across Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah, which can be both beneficial for water resources and challenging for outdoor recreation.

What is a "Monsoon"?

A common misconception, when many people hear the word "monsoon," they think of a massive downpour that persists for a long time. In actuality, a monsoon refers to a seasonal weather pattern or wind shift that results in frequent showers or thunderstorms across a region during a particular time of year.

The most significant monsoon on a global scale is the Asian Monsoon, which affects the Himalaya Range in addition to the tropical and subtropical regions of India and Southeast Asia. The North American Monsoon is smaller and less intense by comparison but is still an extremely important pattern across the Southwest U.S.

What Causes the North American Monsoon?

The North American Monsoon originates over the highlands of Central and Northern Mexico in June, where an area of high pressure in the upper levels of the atmosphere typically sets up. Instead of westerly winds aloft that are more common in the cooler months, winds aloft rotate clockwise around the high pressure center, drawing in moisture from the east and the south.

Rich moisture arriving from the Gulf of Mexico, South Pacific Ocean, and Gulf of California in combination with intense solar heating and warm air will result in near-daily rounds of showers and thunderstorms developing over the higher terrain of Mexico as the monsoon gets going in June.

The elevated terrain of Central and Northern Mexico also aids in the frequent development of showers and thunderstorms. As rainfall becomes abundant, surface moisture left over from prior days' rain events will recirculate back into the atmosphere through daytime heating, further strengthening the monsoonal pattern.

This is how the pattern typically shapes up during June as the monsoon begins in Mexico.

In addition to the traditional moisture sources, as the season wears on and the monsoonal pattern shifts northward into the U.S., tropical storms and hurricanes in the Eastern Pacific can also transport moisture into the monsoonal flow, which can result in an added boost.

When Does the Monsoon Typically Impact the Southwest U.S.?

The average position of the high-pressure center in the upper levels of the atmosphere will drift northward as the summer wears on, and with it, monsoonal moisture eventually surges northward into the U.S.

Monsoon season in the U.S. varies from year to year, but on average, it gets going by early July and persists into early September, before weakening and eventually ending by mid to late September. However, in some years, the monsoon can get going in the U.S. as early as June and persist as late as early October.

Technically, Monsoon Season in the U.S. as defined by the National Weather Service, lasts from June 15 to September 30, but in reality, the window is usually shorter than this.

The peak intensity of the monsoon, when moisture levels are at their highest and heavy rainfall and thunderstorms are most frequent, typically occurs in late July and early August.

Which States and Mountain Ranges are Most Impacted by the Monsoon?

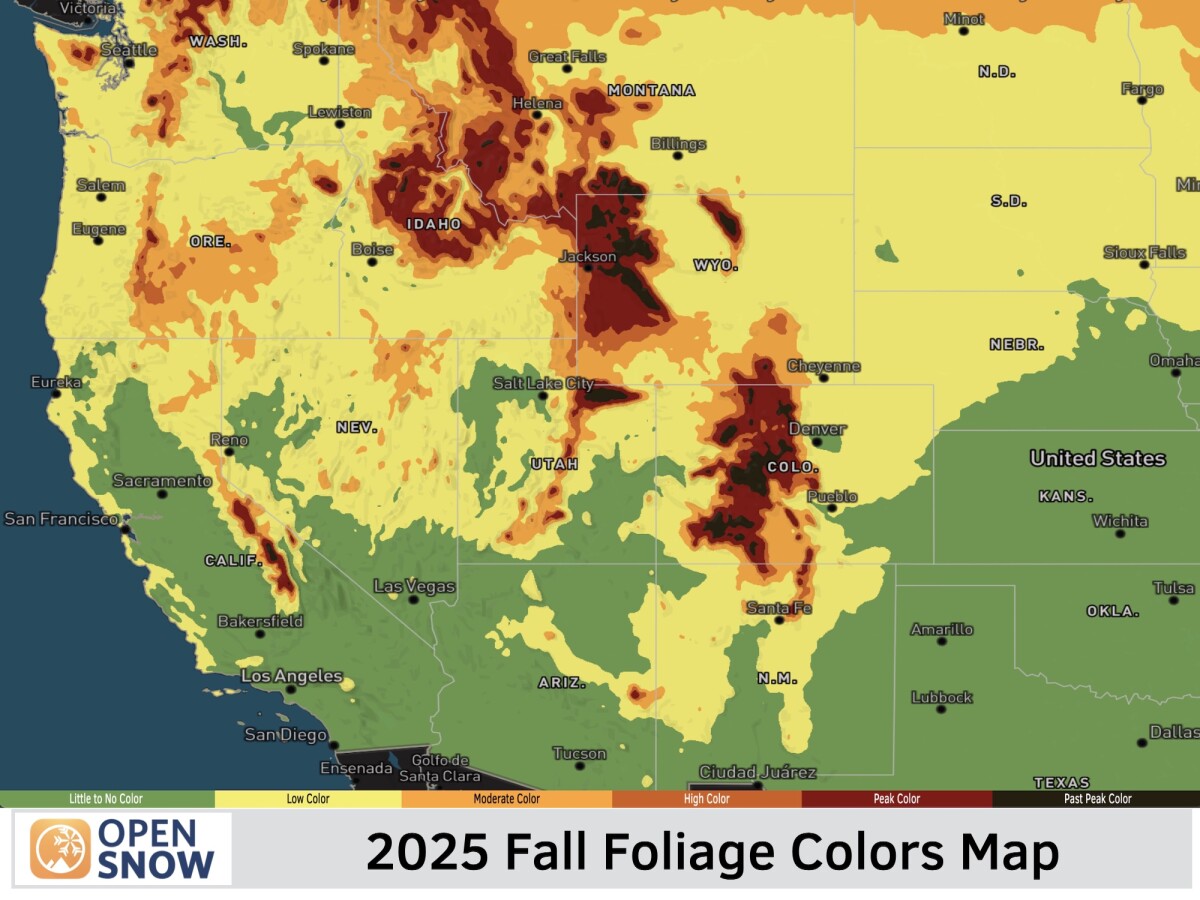

The areas most heavily influenced by the monsoon include New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Southern/Eastern Utah. However, monsoonal surges also occur north and west of these "core" areas at various times during the summer.

The location of the high-pressure center in the Western U.S. and the winds flowing around the high-pressure center are major factors in determining the "flow" of monsoonal moisture. Low pressure troughs can also set up over the Western U.S., which can also influence moisture transport.

Some of the higher mountain ranges popular with peak baggers that are most susceptible to thunderstorms on a near-daily basis include the San Juan Range, Sangre de Cristo Range, Sawatch Range, Elk Range, and Front Range.

Also, thunderstorms are very common across the Colorado Plateau national parks of Southern Utah and Northern Arizona (including Zion and Grand Canyon), as well as nearly all mountainous regions of New Mexico. Thunderstorms become a near-daily occurrence for weeks on end during active monsoon patterns across these mentioned areas.

Monsoon-related thunderstorms gradually decrease in frequency heading north and east of the core areas. Storms can still occur somewhat regularly across the Uinta Range of Utah, the Park Range of Colorado, and the Wind River and Snowy Ranges of Wyoming.

Occasional westward and northward surges of monsoon moisture can result in active thunderstorm periods across the Sierra Nevada Range as well as the Wasatch, Teton, Sawtooth, Madison, Gallatin, Bitterroot, and Beartooth Ranges, but this occurs less frequently compared to areas further south and average rainfall in July and August across these ranges is much lower.

Monsoonal moisture surges into the Pacific Northwest and far northern Rockies (such as Glacier National Park) are much less common, but can occur under the right setup.

The map below shows the average number of thunderstorm days per year, and the areas most heavily influenced by the monsoon can easily be seen.

Outdoor Recreation Weather Impacts During Monsoon Season

Monsoon moisture surges can significantly influence outdoor recreation across the Western U.S. Depending on the location and the characteristics of a particular monsoon pattern, impacts can include frequent and deadly cloud-to-ground lightning, heavy rainfall, flash flooding, damaging wind gusts, and wildfires.

Lightning

When significant amounts of subtropical moisture associated with the monsoon arrive over an area, it often results in greater instability when combined with surface heating from the sun. This, in turn, can lead to significant amounts of cloud-to-ground lightning occurring with any thunderstorms, which is especially dangerous for peak baggers, above-treeline hikers, and canyon country hikers.

Learn More → Lightning Safety in the Mountains

Heavy Rain and Flash Flooding

Monsoon season is when flash flooding concerns are at their highest across the slot canyons, dry washes, and desert regions of Southern Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico.

It's important to pay attention closely to weather forecasts to monitor rain and flash flood potential before venturing out into canyon country, as the soil in these areas does not absorb heavy rainfall, and previously dry areas can turn into raging torrents within a matter of minutes.

Flash flooding can also occur across the Rocky Mountains and can result in rapid rises in river levels and also landslides/mudslides. The Big Thompson Canyon Flood of 1976 and the Boulder/Estes Park Floods of 2013 both occurred during active monsoon periods.

Damaging Wind Gusts

Strong and occasionally severe thunderstorms can develop during the monsoon and produce strong outflow wind gusts in excess of 60 mph. Strong winds can occur in conjunction with heavy rain, but are most common on the "fringe" of monsoonal moisture plumes when there is just enough moisture for thunderstorms to develop, but not enough to produce heavy rain.

In these borderline monsoon setups, dry thunderstorms are more common and tend to produce higher wind gusts. This is because much of the precipitation under dry thunderstorms will evaporate before reaching the ground, and the evaporation process causes air associated with the downdraft to accelerate as it approaches the surface.

Wildfires

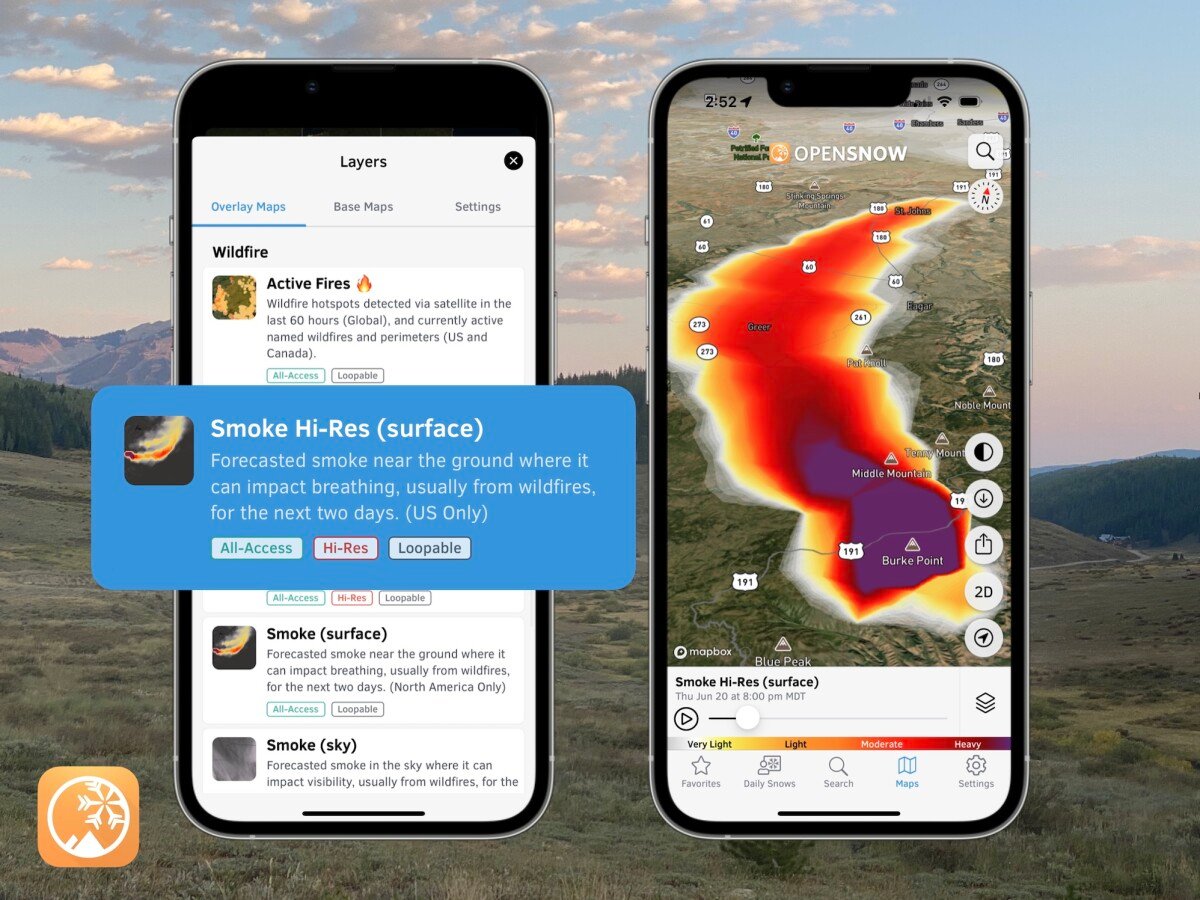

Areas on the fringe of a monsoonal moisture surge with less moisture available can also see a greater risk of lightning-triggered wildfires if vegetation fuels are dry and fire-prone. This is common across the Sierra and the Northern Rockies, where sometimes there is just enough moisture to trigger thunderstorms, but only enough to produce light and inconsistent rainfall.

Dry thunderstorms can also occur at the very beginning of a multi-day moisture surge, as the leading edge of moisture often arrives at higher altitudes, whereas it often takes a day or so for the lower levels of the atmosphere to become sufficiently moist enough for wetting rains.

Gusty outflow winds associated with dry thunderstorms can also significantly influence fire behavior from ongoing fires, and rapid wind shifts can threaten areas that were previously considered safe from a fire.

How Does the Monsoon Vary Year to Year and Can it Be Predicted?

The monsoon can vary significantly in intensity, location, and duration from year to year. In some years, the monsoon can be very weak and short-lived, and produce little rainfall across the areas that usually depend on it. Drought and wildfire ramifications can be significant across New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado if a particular year's monsoon significantly underperforms.

2020 is a prime example of a monsoon season that was practically nonexistent, and by no coincidence, Colorado had one of its worst fire seasons on record.

The seasonal predictability of monsoon seasons in advance is generally low, though there are a few factors that scientists have identified that can contribute to a stronger (or weaker) monsoon season.

1) Ocean Temperatures – Ocean temperatures in the Gulf of California can play a major role in the strength and frequency of monsoon moisture surges into Arizona, as well as Utah and Western Colorado, with above-average ocean temperatures favoring more moisture.

Areas east of the Continental Divide, including New Mexico and the eastern ranges of Colorado, appear to be more influenced by the Gulf of Mexico than the Gulf of California.

Generally speaking, above-average ocean temperatures in these source regions increase the potential for "richer" moisture to work its way northward into the U.S., thus increasing the potential for an active monsoon.

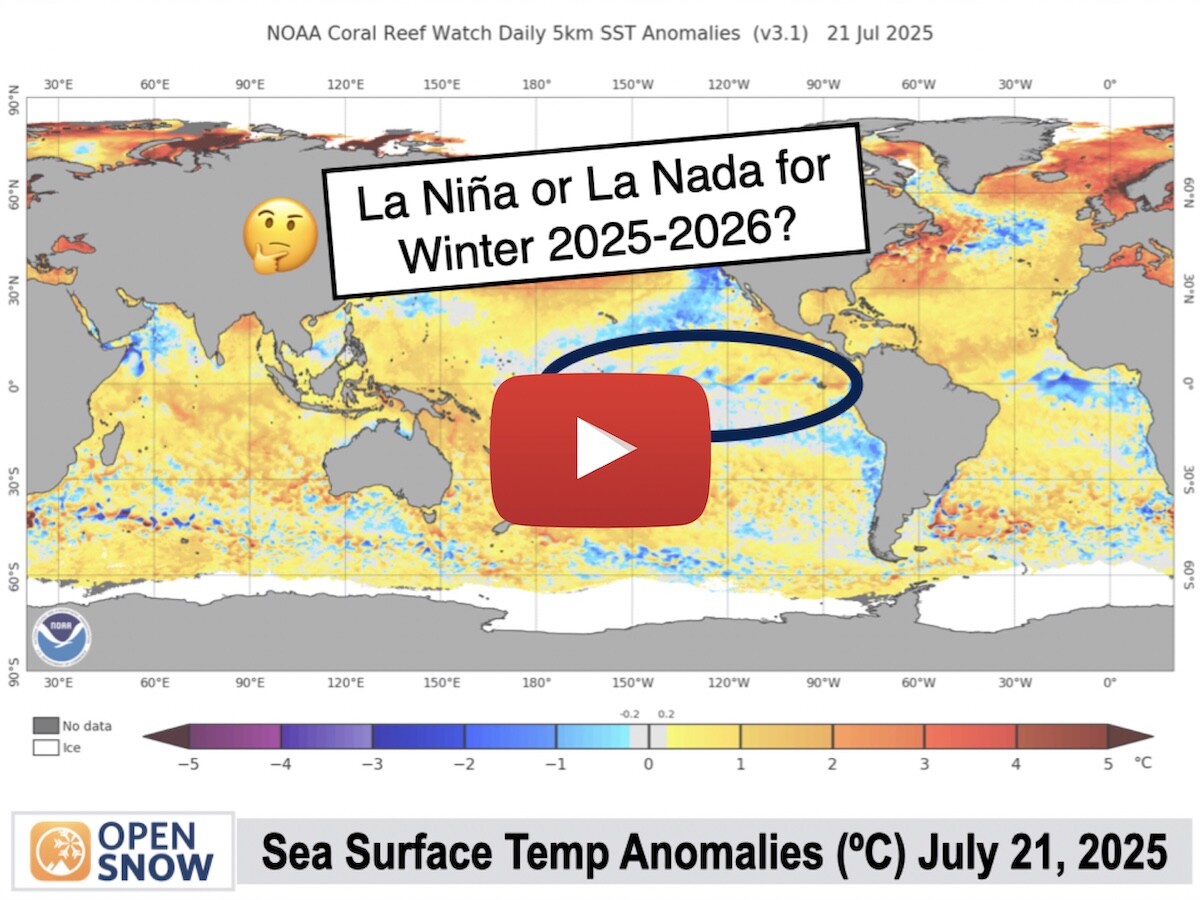

2) El Nino and La Nina – There are some correlations suggesting that summers with La Nina conditions tend to favor stronger monsoons, whereas summers with El Nino conditions tend to favor weaker monsoons.

3) High Pressure in the Southwest and Spring Snow Cover – The position, strength, and movement of the seasonal high pressure area that develops over the Southwest and South Central U.S. influence the monsoon, since clockwise (anticyclonic) winds around the high transport moisture from the oceans.

It may seem counterintuitive, but stronger high pressure areas that develop and migrate northward earlier in the summer not only bring extreme heat early in the summer but also tend to favor moisture reaching the Southwest earlier in the monsoon season and can lead to a wetter monsoon season overall.

Snow cover can actually be a factor here as well. Above-average snow cover in the spring across the Southwest and the Rockies often results in the delayed development and northward migration of the high pressure ridge, which can delay and/or weaken monsoon season.

This is because a greater amount of solar radiation in the spring is used to melt snow cover rather than heat up the land. But heavy winters followed by warm early springs that lead to early snowmelt can potentially negate the snow cover feedback.

Is Climate Change Influencing the Monsoon?

The connection between climate change and the North American Monsoon is uncertain. In a warming climate, there are both factors that could lead to wetter monsoon seasons (warmer air can "hold" greater amounts of moisture) and drier monsoon seasons (soil moisture can evaporate more easily under hotter temperatures).

So far, research has not indicated any significant long-term trends in monsoon season rainfall due to climate change.

Questions? Send an email to [email protected] and we'll respond within 24 hours. You can also visit our Support Center to view frequently asked questions and feature guides.

Alan Smith

About The Author