News

By Alan Smith, Meteorologist Posted 1 year ago May 8, 2024

Transition to La Niña, Western U.S. Summer 2024 Outlook

As of early May 2024, El Niño is rapidly weakening due to the cooling of ocean temperatures in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific Ocean, and confidence is increasing that La Niña conditions will develop during the summer of 2024.

From approximately May 2023 through April 2024, El Niño conditions were present as ocean temperatures in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific were warmer than average. However, we are about to reverse course as ocean temperatures in the Eastern Equatorial Pacific have cooled to near average and are expected to become colder than average over the summer.

The transition from El Niño to La Niña conditions is occurring just as we are about to head into the summer season in the Northern Hemisphere.

The graph below shows the probability of La Niña, El Niño, or Neutral conditions for a given 3-month period with each period denoted by the first letter of the month (for example, JJA is denoted for the 3-month average for June, July, and August).

Summer seasonal weather patterns are notoriously difficult to predict in advance, even more so than winter. However, there are some seasonal weather signals that arise across the Western U.S. when we examine past summers featuring a transition from El Niño to La Niña.

First, we have identified five analog years since 1991 in which El Niño conditions dissipated in the late winter or spring and La Niña conditions developed during the Northern Hemisphere summer. We then examine each of these summer seasons (June-September) based on 30-year climatological averages from 1991-2020. These analog years include 1995, 1998, 2007, 2010, and 2016.

Given the rate of warming that is occurring in the global climate over the long term, it makes sense to examine more recent years based on 1991-2020 averages rather than diving too deep into the past. New 30-year averages are determined at the start of each decade.

Prevailing Large Scale Patterns

During a typical summer season, the jet stream gradually weakens and lifts northward into Canada over time. Periodic late-season cool and wet spells in the Northwest and Northern Rockies during the month of June give way to hotter and drier conditions across much of the West by July and August, while the Southwest and the Central Rockies see an uptick in thunderstorms and rainfall in mid to late summer due to the North American Monsoon.

During past El Niño to La Niña transition summers, there is a fairly consistent signal in which low pressure troughs are more common than normal across the Northwest U.S., while stronger and more persistent high pressure ridges are more typical across the Eastern U.S.

The map below indicates the departure from normal "heights" in the upper atmosphere at approximately 18,000 feet above sea level. Positive (+) anomalies indicate higher heights and stronger "ridging" than normal, and negative (-) anomalies indicate lower heights and more "troughing" than normal.

While the jet stream is weakest during the summer months, during El Niño to La Niña transition summers, the jet stream tends to dip into the Western U.S. more than normal with above-average wind speeds noted in the upper levels of the atmosphere at 250 millibars (about 34,000 feet).

Here are some of the key weather pattern trends we have found during El Niño to La Niña transition summers, when examining the four-month period from June through September:

- Temperatures tend to be below average near the West Coast and above average along the eastern side of the Continental Divide.

- Rainfall tends to be near to above average for most of the West, except for the Colorado Front Range and New Mexico which tend to be drier than average.

- Monsoon season tends to be healthy across the Four Corners region in terms of rainfall, most notably in Arizona, with periodic northward intrusions of moisture also occurring.

- Winds tend to be stronger than normal across the Rockies, which could impact high-elevation hiking/climbing, water activities, and fire danger.

- June tends to be the biggest "wild card" month in our analog years, with some Junes featuring hot and dry conditions, and others featuring much cooler and wetter than normal conditions.

Let's take a closer look at seasonal and regional trends for the five analog years for the summer season from June through September...

El Nino to La Nina Transition Summers – Temperatures

The four-month period from June to September tends to be cooler than average across the West Coast and Great Basin, likely in response to more frequent low pressure troughs in this region. Temperatures tend to be slightly hotter than average on the east side of the Continental Divide.

Image: Departure from average temperatures from June through September during the analog summers of 2016, 2010, 2007, 1998, and 1995. Yellow/red areas show hotter than average temperatures, and green areas show cooler than average temperatures.

Early summer (June) can go either way with some of the analog years featuring widespread above-average temperatures, and others featuring widespread below-average temperatures.

During mid-summer (July and August), there is a below-average temperature signal from Central California to the Pacific Northwest, and an above-average temperature signal in the far Southwest and on the east side of the Rockies.

Image: Departure from average temperatures in July and August during the analog summers of 2016, 2010, 2007, 1998, and 1995. Yellow/red areas show hotter than average temperatures, and green areas show cooler than average temperatures.

In late summer (September), we continue to see a below-average temperature signal along the West Coast, especially in California, while temperatures are more likely to be warmer than average across the Rockies with the strongest signal east of the Continental Divide.

Overall, history tells us that the West Coast may see fewer severe or prolonged heatwaves than normal this summer, while the east side of the Continental Divide is more favored for above-average summer temperatures. The Southwest U.S. could also see an elevated risk of extreme mid-summer heat.

El Nino to La Nina Transition Summers – Precipitation

Summers tend to be wetter than normal across a large portion of the West, with the strongest signals across the Northern Rockies. Exceptions include New Mexico and the Front Range of Colorado where summer rainfall tends to be below average.

Image: Departure from average rainfall from June through September during the analog summers of 2016, 2010, 2007, 1998, and 1995. Green areas show above-average rainfall, and yellow and red areas show below-average rainfall.

Typically, the Northwest and West Coast, and areas west of the Divide in the Northern Rockies, experience a distinct dry season in July and August with low rainfall due to the semi-permanent area of high pressure that migrates into the Northern Pacific Ocean, which acts as a barrier to moisture reaching this region.

The wet anomalies we see for the Northwest and Northern Rockies could indicate a higher frequency of wet Pacific storm systems in June and September, with perhaps more frequent rain events than usual during the July-August dry season.

The Northern Rockies (especially Montana), being further away from the cold Pacific Ocean, are also more likely to see thermally-driven thunderstorms when upper air disturbances move through in the summer, and this region can occasionally see monsoonal moisture intrusions from the south as well.

Both of these setups could occur with greater frequency this summer due to more frequent low pressure troughs noted in analog years.

What About the Monsoon?

Monsoon season forecasting is tricky because prior research has yet to find conclusive evidence that can be used to reliably predict the strength and persistence of the North American Monsoon on a seasonal basis. This is one of the bigger mysteries in seasonal forecasting, at least in North America.

However, we did find some signals when looking at precipitation anomalies during the peak monsoon season of July and August.

In four of the five analog years examined, monsoon season rainfall was above average for at least a decent portion of the Four Corners region, with only one year (1995) being below average across the board.

Looking at the five years combined, we see the strongest signal for monsoon season rainfall across Arizona, Western Colorado, and Western New Mexico with below-average rainfall favored across Central and Eastern New Mexico.

Image: Departure from average rainfall for July and August during the analog summers of 2016, 2010, 2007, 1998, and 1995. Green areas show above-average rainfall, and yellow and red areas show below-average rainfall.

Low pressure troughs tend to be more favored in the West Coast and Northwest vicinity during El Niño to La Niña transition summers. This is important because winds blowing from the south or southwest on the eastern side of a trough can transport monsoonal moisture from the subtropics into the Southwest and Southern Rockies, and occasionally further north.

The position and movement of troughs can affect who sees moisture and who doesn't in mid-summer. Stationary troughs near the West Coast or Great Basin can lead to a consistent flow of moisture from the south or southwest, whereas troughs that move across the Central Rockies can scour our and suppress moisture well to the south, resulting in periods of drier conditions.

Another uncertainty with monsoon season is the timing. On average, monsoon season begins in the Southwest U.S. during early July and peaks in late July and early August, before gradually fading in September. However, the timing of both the onset and demise of the monsoon can vary significantly from year to year.

Wildfires and Smoke

Fire activity is difficult to predict in advance as it depends on numerous pre-existing and current factors in terms of weather and vegetation fuels, not to mention human activity.

We do have two things working in our favor that could contribute to this not being too bad of a fire season. First, we are coming out of a healthy snow season across most of the West Central and Southwest U.S., and second, El Nino to La Nina transition summers tend to be more favorable in terms of temperature and moisture.

Keep in mind, however, that if a prolonged hot and dry spell manages to develop over a region along with any combination of wind and/or dry thunderstorm outbreaks to follow, that could quickly change the fire and smoke situation. Fire danger depends on short-term weather patterns just as much as pre-existing long-term patterns.

Below is a four-month significant wildfire potential outlook produced by the National Interagency Fire Center.

The biggest takeaways are elevated fire danger in New Mexico where snowpack has melted quickly due to recent warm and dry weather, and across Northwest Washington where snowpack was below average this winter. Also, above-average fire potential is projected in Southern Idaho and Northern Nevada.

Stronger than Normal Winds this Summer?

One interesting signal we found is higher-than-normal wind speeds across the Rockies during El Niño to La Niña transition summers. In the map below, green and yellow colors indicate above-average wind speed anomalies.

This does make sense, however, given the signal for more low pressure troughs along the West Coast and Northwest. This tends to result in tighter pressure gradients that can lead to stronger winds near and downwind of a trough.

Add in the elevated terrain of the Rockies, and climbers and hikers may have to deal with stronger winds compared to a typical summer. Keep in mind, however, that winds vary substantially on a day to day basis.

One potential downside of the stronger winds is that it could lead to higher fire danger in areas where vegetation fuels become abnormally dry. When prior conditions are favorable, wind is the top contributor to rapidly-spreading fires.

Also, stronger winds in the middle to upper levels of the atmosphere could potentially transport smoke across greater distances in the event of large wildfires.

What About Western Canada?

Unfortunately, past monthly, annual, and seasonal climate data on a large scale is limited for Canada compared to the U.S.

However, based on the limited data that is readily available, there appears to be a slight bias toward above-average rainfall and above-average temperatures in Southern BC and Alberta during El Niño to La Niña transition summers.

Environment Canada has highlighted most of Western Canada as having above-average wildfire risk this summer, as this area has been in a drought since last year with no improvement this year following a below-average snow season.

One More Wild Card – Eastern Pacific Hurricanes

Last year was a very active hurricane season in the East Pacific, and we saw moisture from some of these hurricanes reach the Western U.S. and contribute to rainfall.

It's not uncommon for the remnants of tropical moisture to reach the Southwest U.S., often helping to enhance the flow of monsoonal moisture. However, we did see an exceptional event last year with Hurricane Hilary, which maintained tropical storm strength by the time it reached California on its northward journey (a very rare occurrence).

The remnants of this storm brought moisture to typically dry parts of the West, resulting in widespread heavy rainfall, including record-breaking summer rains in many areas from California to Idaho.

Last summer, we were in an El Niño phase which favors above-average Eastern Pacific hurricane activity. This summer, we will be transitioning to a La Niña which favors below-average hurricane activity. As a result, it would be reasonable to expect fewer impacts from the remnants of tropical activity in the Western U.S. this summer.

Limitations of Seasonal Forecasting

While these past signals are fun to examine and offer some insights as to what we might expect this summer, keep in mind that seasonal outlooks should always be taken with a grain of salt. There are many factors in the atmosphere that cannot be anticipated months in advance and every year is unique in its own way.

We will continue to monitor the emerging La Niña as the summer progresses and stay tuned later this summer as we start to dive into winter outlooks for 2024-2025.

Weather Coverage For Every Season

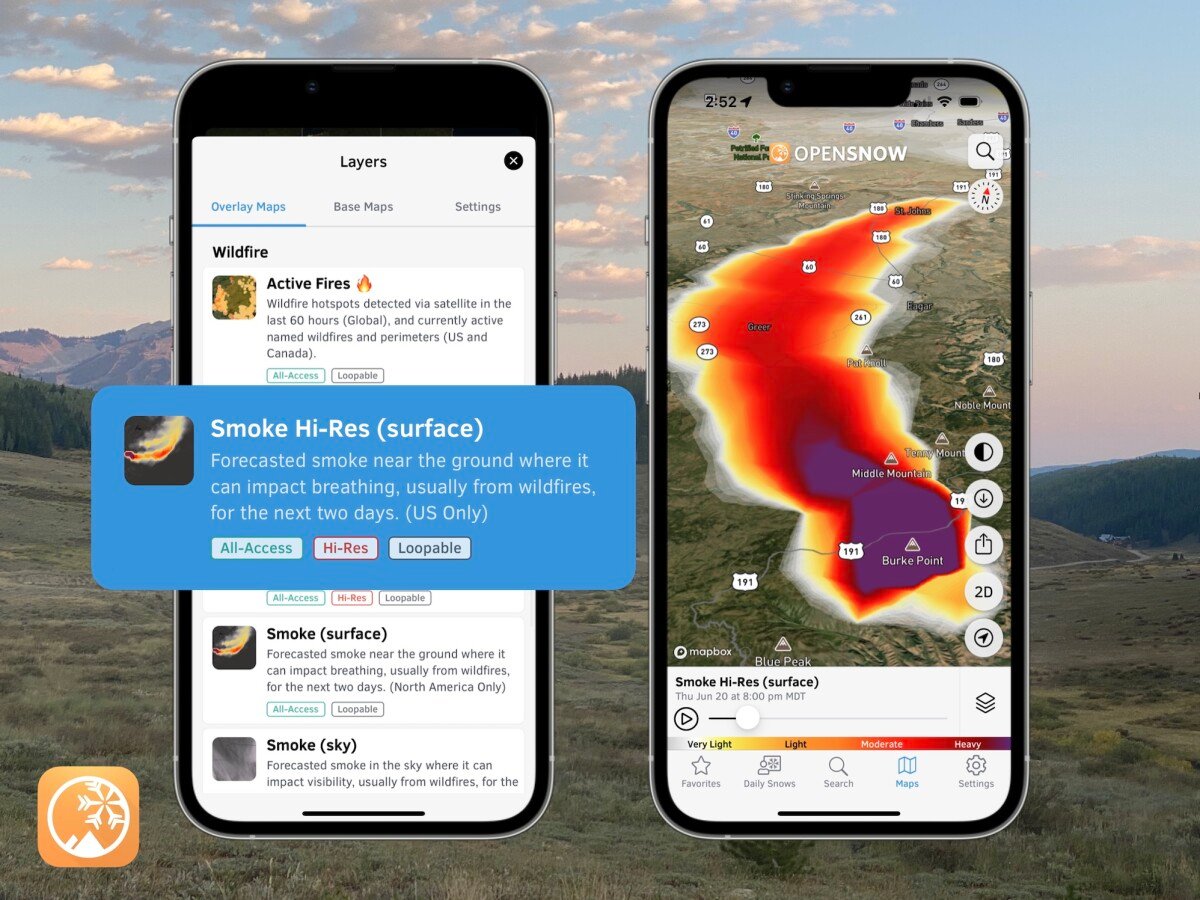

Don’t forget that you can use OpenSnow as your go-to weather app, no matter the season.

Switch to using your "Summer" favorites list, check the "Weather" tab on both the Favorites screen and any location screen, and avoid poor air quality & incoming storms with our summer-focused map layers in the OpenSnow app.

You can also view the hourly forecast for the next 10 days for any location on Earth in OpenSnow:

- Go to the "Maps" tab.

- Tap anywhere or search for a city.

- Tap "View Forecast".

View → Summer Forecasts

Alan Smith

About The Author